You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Is it akin to this?

https://www.ft.com/content/84892c56-1a17-11e7-bcac-6d03d067f81f

https://www.ft.com/content/84892c56-1a17-11e7-bcac-6d03d067f81f

When the local council on the Isle of Wight off Britain’s south coast prepares to make a £100m punt on the commercial property market, something strange is surely afoot. Yet the decision, taken earlier this year on the genteel island that was home to the ageing Queen Victoria and the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, is far from unique. In fact the Isle of Wight will be a latecomer to a local government real estate party that has acquired serious momentum.

Across the UK, local councils have been plunging into the commercial property market or embarking on residential property development, either for sale or for the private rental market.

“They are punting like drunken sailors all around the country,” says a bemused fund manager who has been outbid by local authorities on more than one investment this year. The driving force behind this hedge fund-style activity is the same one that pushed local governments in Japan to buy property in the 1980s bubble and that now prompts China to encourage manic property development from its municipalities: the need to plug gaps in their budgets after years of funding cuts from the central government. UK local councils are engaging in what is known in the financial jargon familiar to hedge fund managers as a carry trade — a form of arbitrage whereby they borrow at rates much lower than private sector borrowers can obtain in order to invest in property that shows a much higher yield.

Money borrowed at 2.5 per cent or so is typically going into property yielding 6-8 per cent or more. Where Britain differs from bubble-period Japan is in the financing of the property binge, which comes mainly from the public sector. If local authorities can outbid almost all other participants in the commercial property market, it is because they have access to cheap and flexible funding from the Public Works Loan Board, an arm of the Treasury that has been helping finance capital spending by local government since 1793.

Its interest rates are linked to those in the gilt-edged market which have been at exceptionally low levels since the financial crisis of 2007-08. At the end of 2016, according to estate agents Colliers International, local councils were able to access a 45-year loan from this ancient body at a fixed rate of 2.45 per cent. For some, this is alarmingly redolent of earlier fiascos in the UK, especially the financial crisis.

Lord Oakeshott, chairman of Olim Property, investment manager of £650m of commercial property for pension funds, charities and investment trusts, says: “English councils punting on property is an accident waiting to happen.” He adds: “There are real echoes here of Northern Rock, where many punters were lent all the purchase price of a property, and the Icelandic bank scandals, where councils played a market they didn’t understand for short-term income gain.”

*** The spending spree has been at its fiercest for shopping centres. Surrey Heath borough council last year spent £86m on The Mall, Camberley; Canterbury city council bought half of the £79m Whitefriars centre in the cathedral city, Stockport borough council bought the Merseyway centre in the town for £75m, while Mid Sussex district council spent £23m on another in Haywards Heath. They have also been busy buying offices, retail warehouses, industrial parks, solar farms, hotels, garages and country clubs. Increasingly this speculative investment activity is taking place beyond council boundaries. Big spenders: Portsmouth City Council's civic offices © Alamy

These mainly English public sector investors are now a force in the market. According to Mat Oakley of estate agents Savills, they bought £1.2bn worth of property in 2016 and had spent at least £221m by late March this year. Agents talk of a pipeline of current deals running into several hundred million pounds. Everywhere the motive is the same: to generate additional revenue to maintain services — housing for the elderly, children’s centres, libraries and the rest — that might otherwise fall victim to the Treasury’s remorseless squeeze on local government finance.

Another motivating factor is a change in local government funding rules. From 2020 local authorities will be allowed to keep 100 per cent of their tax revenues from businesses, rather than the 50 per cent they can at the moment. This is intended to compensate them for the shrinkage of grants from central government. It gives them a strong incentive to promote growth in their local economies to expand their business tax base. Property news Grosvenor Group warns on ‘chilling’ London property market Duke of Westminster’s property company saw steep drop in UK returns in 2016 By far the biggest local authority bet in commercial property to date is the purchase last September by Spelthorne borough council of BP’s office park at Sunbury-on-Thames for a reported £360m. Finance for the Surrey site, which consists of 11 office blocks, was provided by the PWLB in the form of 50 separate loans with maturities running from one to 50 years, amounting in total to £377.5m.

This, the council told the Financial Times, covers transaction costs such as stamp duty as well as the purchase price. The interest rates on this so-called blended annuity loan run from 0.83 per cent on the shortest-dated loans to a maximum of 2.26 per cent for longer loans. Under the sale-and-leaseback scheme, the oil company will be a tenant of the council for a minimum period of 20 years. Spelthorne declined to reveal the initial yield on the investment. In a press release explaining its purchase of the largest privately owned office park in the UK, the council said funding from central government would be withdrawn completely in 2017-18, so it had been forced to find innovative ways to fund services and create new revenue. It has also been encouraging economic development within the borough to help stimulate growth in business rates. These are the same factors behind the wider local government spending spree in property.

*** For Spelthorne the £377.5m borrowings are huge in relation to its gross assets of £87.7m, net assets of £39.7m and gross income last year of £73.9m. So the BP office park purchase transforms the nature of the council. In balance sheet terms, Spelthorne is now a property company with a sideline in providing local government services. Even for the best of motives, it is a highly risky bet. Local government officials refer to financing from the PWLB as “prudential borrowing” or Pru-Bo, an oxymoronic label given the dangers implicit in the big bets being taken. The history of local governments punting in markets is not reassuring.

Most of the bets taken by Japanese cities in the 1980s generated huge losses in the 1990s, doing considerable damage to the public purse. In the US, such speculation has led to bankruptcy — most notably at Orange County in California, which was forced to declare itself bankrupt in 1994 after losing $1.6bn on derivatives trading. Core responsibility: social housing in Bristol © Getty The difficulty for financially stretched councils in the UK, as Jennifer Wong, a vice-president at the Moody’s rating agency in London points out, is that this is “quite different territory for local government in terms of risk profile”. Local authorities are exposed to a new credit risk because the revenues from the properties are inherently uncertain.

In their investment in the housing market, authorities also face the same early-stage construction risks as private developers. On completion, the properties are exposed to market fluctuations. The greatest risk arises in commercial property, relating to financial gearing, or leverage, whereby borrowing magnifies the potential profits or losses that result from changes in the market value of the asset. Property market sources claim that many of these local authorities have been overpaying and financing their purchases on a 100 per cent loan-to-value basis. Many PWLB loans are for much longer periods than the leases the authorities have bought, so they could face an exit penalty on early repayment.

Borrowing on the full value of the property is especially tempting because borrowing at less than 100 per cent means the investment in property could squeeze spending on social priorities, as any initial downpayment would come out of the current budget. Local government property spending: key figures The Merseyway Shopping Centre, bought by Stockport borough council © Alamy £1.2bn Value of property bought by English public sector bodies in 2016 £221m Value of property bought by English public sector bodies in 2017, up to late March £94bn Forecast total revenue expenditure for English local governments in 2016/17, 10% down on 2010/11 £65.3bn Total outstanding loans issued by the Public Works Loan Board. Its remit allows for outstanding loans of £95bn At the full 100 per cent a property can immediately make a positive contribution to the local authority budget as it pockets the margin between the borrowing cost and the higher initial yield on the property. The question then is whether it will stay positive. Tenants can, after all, go bust or the value of the property may turn out to have fallen when the lease expires. In the worst-case scenario the local authority buys properties that are very large in relation to its revenue-raising potential and which turn out to be dud and illiquid investments. With the council’s finances dented by property losses, the rise in revenue or cuts in services required to meet its statutory commitment to balance the budget might be so outlandish that a central government bailout would be unavoidable.

*** This incentive to borrow to excess indicates that the Treasury is helping to create an incipient public sector credit bubble while entrenching a culture of incautious risk-taking in local governments. FT Comment A quirky and hazardous corner of British public finance It is not sensible for an offshoot of government to compete with commercial banks As well as requiring much less due diligence than a commercial bank, the PWLB does not apply a loan-to-value discipline, whereby borrowings are capped at a given percentage of the purchase price. And it has plenty more largesse to distribute because its outstanding loans, which stood at £65.3bn in March 2016, are permitted under its current remit to rise to £95bn. The larger local authorities are also now turning to the capital markets where, as sovereign borrowers, they can issue index-linked debt on terms even more favourable than those available from the PWLB. There will in due course be a reckoning. Since the Brexit referendum a conspicuous casualty in property has been the shopping centre market, which has also been badly hit by the rise of online retail. Mike Prew, managing director and head of real estate at investment bank Jefferies International, calls it “a slow-motion train wreck”. Since local authorities revalue their properties annually and their auditors are required to report on whether their investments represent value for money, any damage will become public knowledge. There is a larger irony in the role of the Treasury: under George Osborne and now Philip Hammond, it has caused local authorities to bear the brunt of its commitment to austerity. Yet via the PWLB it is simultaneously encouraging lowly paid local authority bureaucrats to behave like entrepreneurial risk takers on cheap public money. The verdict of Olim’s Lord Oakeshott is telling: “As with Northern Rock and Icelandic banks, there’s a serious systemic risk to the property market and financial stability developing here, but the Treasury and Bank of England are fast asleep to it yet again.”

davek

Player Valuation: £150m

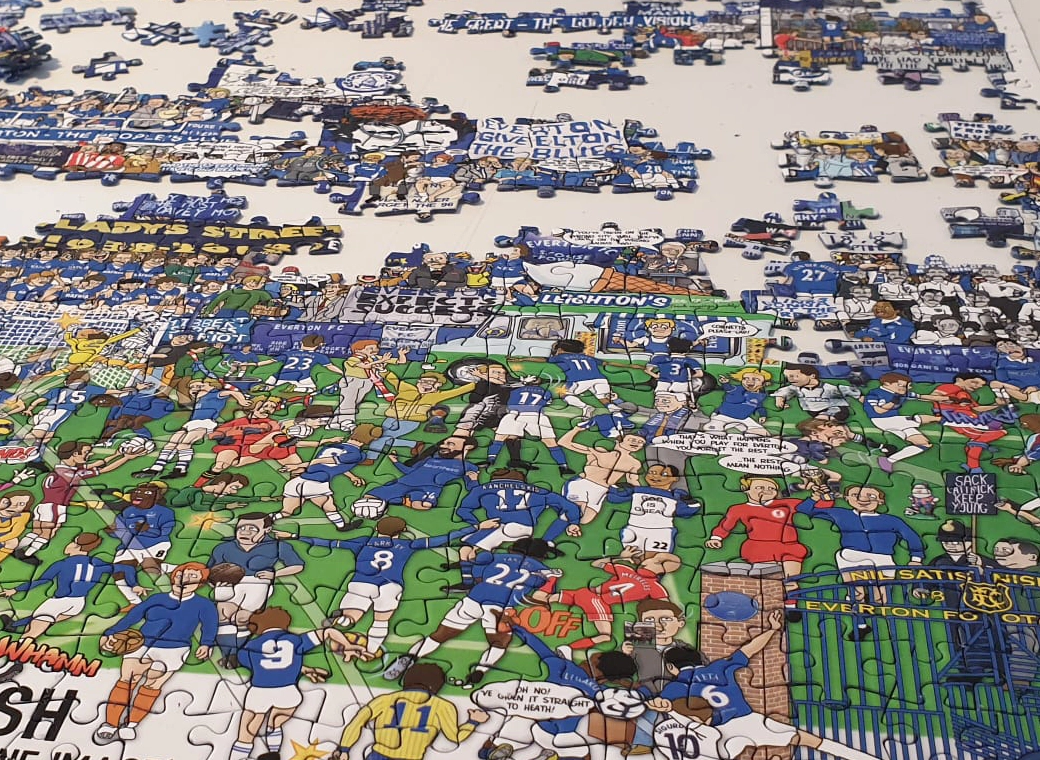

He'll be chuffed with that.@MoutsGoat been busy with his crayola set !

A

Addo

Guest

Fab Four at the bottom Ha Ha Look at that design WTF did DM sort that HaLook at the quality of these images...

...I mean THAT is embarrassing.

BK NO NO DM use felts.

Mikeonlythebestwilldo

Player Valuation: £20m

He got first prize on blue peter didn't he !He'll be chuffed with that.

Do people genuinely believe Moshiri isn't going to rent those offices to the club?

We've just rented different offices from another landlord. Whoopee.

Of course it’s a lease and I bet it will be at OMR.

Fab Four at the bottom Ha Ha Look at that design WTF did DM sort that Ha

BK NO NO DM use felts.

What's wrong with that design?

davek

Player Valuation: £150m

Fab Four at the bottom Ha Ha Look at that design WTF did DM sort that Ha

BK NO NO DM use felts.

It's just appalling. Look at the 'kin state of that "legacy" image of one of the country's/Europe's famous old stadiums.

They really dont get the fact that everything they did their was an insult.

TraffordBlue

Player Valuation: £30m

Do people really believe that Joe Anderson is able to commit £300 million from the LCC budgmt without full approval from the council ?? Come on lads a bit of common sense eh...

Mr Anderson says to “the cynics” he’d do the same for LFC. He hopes the funding package will be in place for Everton to build a new stadium. Mr Anderson’s finishes his speech which is met with a round of applause.

Meanwhile over on GOT, the forum has gone in to meltdown about the heartless council/EFC as most members have forgotten or ignored any previous commitment by LCC to the funding from the SPV and have decided that LCC are throwing £300m of their own money at the stadium project.

Azza

Player Valuation: £80m

I cant get my head round it being like that. Like £300m wiped off the LCC budget would never happen. Rightly so.

But other than LCC facilitating a council backed loan, which isnt miles away from the SPV thing.

Odd turn of events.

The SPV at the moment works like this...

We find a loaner for the money.

The council act as a guarantee.

Loan is repaid via the Special Purpose Vehicle

The council get £££ (~£4.4m pa when initially proposed) for basically facilitating the SPV.

I can only assume that say the loan was £300m...

Say a 50 year loan = £6m pa. + interest

Everton would have to pay £6m + interest + £4.4m = >£10m

Maybe the council can get a cheaper loan which means Everton pay don't have to pay the extra for the SPV and the total cost <£10m pa in rent... ?

If that makes sense.

CRIMHEAD

Player Valuation: £40m

Hasn't Spurs gotten tax breaks to build the new stadium? Am I wrong? Thought they were released from affordable housing requirements, some of the up front tax commitments, etc. I know they are getting money from the NFL, so that'll help a bit.What are you on about?

Gladystweet

Player Valuation: £50m

Now it's the turn of the Chairman Bill Kenwright and Major Shareholder Farhad Moshiri.

Haha wait for it

- Status

- Not open for further replies.