Tuesday

'The players think he is good. Therefore he is good.'

Another freezing 7.30 start, another early phone call. Henri's Portuguese girlfriend and agent calls. Much preciousness ensues. One gets the strong impression she is haggling about terms, but isn't quite prepared to discuss the vulgar subject of money as Henri is obviously an artist.

Moyes is clearly exasperated by the conversation, but realises it goes with the territory. 'The thing is, the players think he's good,' Moyes says. 'Therefore he is good.'

The training ground is still frozen, and there is a repeat of yesterday's deliberations. Moyes checks that the Goodison Park undersoil heating has been switched on. Tomorrow he wants to give the players a session on turf at noon - the time of Saturday's kick-off against Southampton. Training is ball juggling in the freezing gym, followed by lots of keep-ball work.

Back in the manager's office after training, the local radio reports that Rodrigo is returning. No one has seen him at Bellefield. On the trip back to Preston, Irvine calls. A local radio report has mentioned a couple of players as Everton targets. He is worried about security of information. Moyes tells him that the Sunday papers associated him with five targets, including the two mentioned by the radio station, and he isn't worried. 'It was bollocks, Alan.'

In the evening Moyes has dinner at home with his wife Pamela and children, David, 12, and Lauren, nine. They will eat together three times this week, which is about par for the course. Blonde, bright-eyed and quick of movement and thought, Pamela is resigned to the downside of being a manager's wife - her husband's endless hours on the road, the late nights, the long periods away. But she is way too smart to complain about her lot. She married David when he was a promising player at Celtic, and stuck with him through the lower divisions of the English league.

His annual salary at Everton is reported to be a basic of £850,000 (although he claims that is a substantial exaggeration). And even before he took the step up from Preston North End, they were able to afford a secluded, newly built mansion, hidden behind farm buildings and the comfortable sprawl of semis half a mile away. Pamela is grateful for the family's financial security, aware that she and David have come a long way together since they met more than 20 years ago at the Winnock Hotel disco in Drymen, just outside the well-heeled Bearsden suburb of Glasgow.

('She saw me once, and, well, that was it,' Moyes once explained to me. Pamela, scandalised, offered a mock punch and insisted that she was the pursued, not the pursuer.)

Whatever happened in their adolescence, what Pamela says in the house, goes. David is currently thinking about moving home. Pamela is cool on the idea. One gets the feeling an imminent move is unlikely.

My own supper is with David Taylor, who is well qualified to talk about Moyes the manager and the man. Taylor, a property developer in his late forties, is a director of Preston, the club at which Moyes forged his reputation. Taylor remembers Moyes's appointment in January 1998 with a wry smile. Preston had come up from the Third Division under Gary Peters the previous season, but were failing in Division Two.

As the club drifted towards the relegation zone, Peters resigned. The board was under pressure to appoint a 'name' - Ian Rush and Howard Kendall were mentioned - but turned to their 34-year-old centre-half and assistant manager. 'We were accused of lacking ambition,' Taylor chuckles. 'The supporters said we were taking the cheap option.'

Moyes made an immediate impression. In the final quarter of that season Preston averaged almost two points per game. 'He did the simple things really well,' Taylor remembers. 'He promised us that he'd not bring in a player unless he was better than the current playing staff. Sounds obvious, doesn't it? But some managers just panic and buy in. David wouldn't do that. By not panic-buying, he demonstrated confidence in his players, which helped engender a sense of loyalty. Moyes stands by his players, and gets them to play for each other, and for him.'

Having fought off relegation, Preston made the play-offs the following season, and were Second Division champions a year later. By then Moyes was beginning to get noticed. He knows Sir Alex Ferguson, and was in line for the job as No 2 at Manchester United following the departure of Brian Kidd, but opted to stay at Preston.

His first season in the First Division was outstanding with the club making it to the play-off final, beating Trevor Francis's Birmingham en route in a celebrated penalty shoot-out. While Francis's brains were publicly trickling out of his ears as he disputed choice of ends, Moyes was all focus and determination, talking to his charges and examining his list of the Birmingham penalty takers. The preceding week in training, the reserves had been told to study videos of Birmingham in penalty shoot-outs, and took kicks against the Preston keeper, David Lucas, each impersonating a Birmingham player.

Preston lost to Bolton in the final, but Moyes was now a hot property. There were approaches from Sheffield Wednesday, Nottingham Forest, Bristol City, and rumours linked him to just about every job that came up, including West Ham and Southampton. For a while he stayed put, biding his time, anxious that when the move came (and nobody doubted there would be a move) it would be the right one.

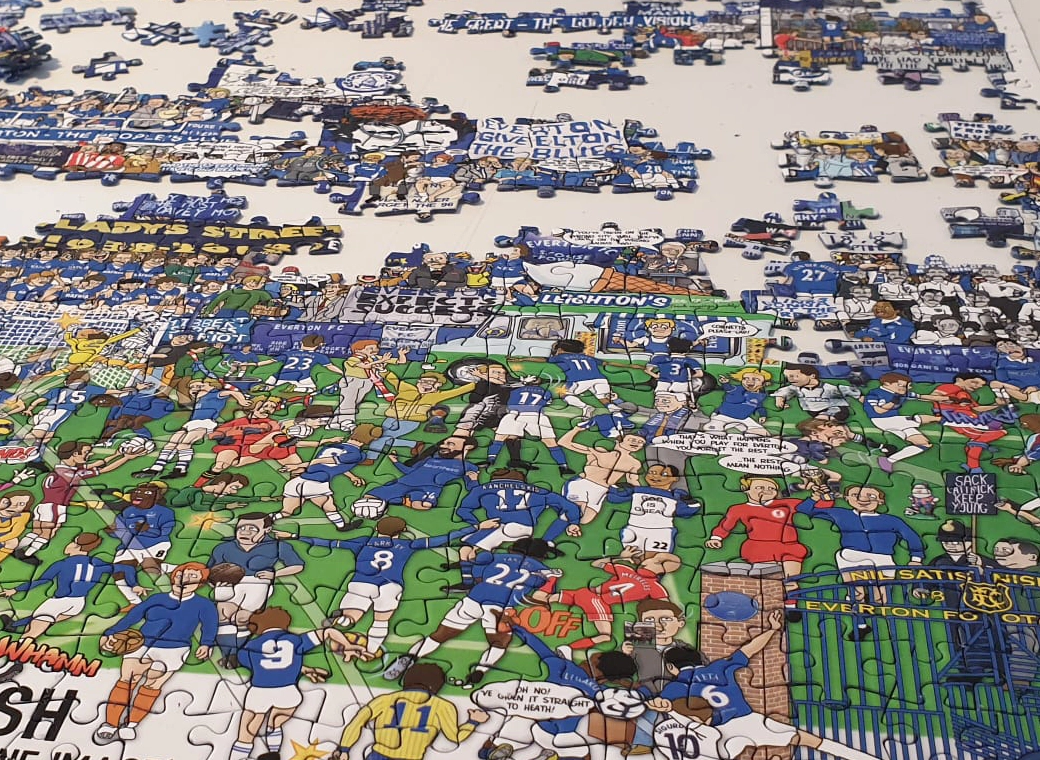

Then, last March, Everton, embroiled once again in a desperate fight against relegation, made an approach. In the Eighties the Merseyside club had been one of the country's biggest, winning the championship twice, and rarely finishing out of the top eight. But the Nineties had seen a desperate and almost continual decline, one that saw them nearly lose their place in the top division. All the same, Moyes was convinced that with a large, passionate support, Everton could be a big club again.

They were the right club - but there was a problem. The then manager was Walter Smith, a gruff but dignified Scot who had enjoyed considerable success at Rangers a decade earlier. Moyes not only respected Smith, he liked him. He would not take the job without Smith's blessing. Moyes went to see Smith. They shook hands.

As for Preston, Taylor says with a shrug that they were resigned to losing their man. A few days before Moyes's departure, the club had sold their star striker Jon Macken to Manchester City for £5m, by far the most they had ever received for a player. Taylor is certain that Moyes was worth far more. Preston couldn't expect anything like that for their manager, but Moyes was under contract and they were able to negotiate substantial compensation. 'We got more for David Moyes than any club ever had for the transfer of a manager,' Taylor says. 'We got an indemnity of a million, plus a bonus if Everton stayed up last season. Plus another if they stayed up this.'

At the time it seemed a very good deal. Last season's bonus was paid and this season's is a formality. Yet, looking back, you can't help feeling they have been shortchanged. 'We didn't think to go for a bonus if Everton got into Europe,' Taylor told me ruefully. 'That would have been fanciful, but they'd have agreed it. I bloody wish we'd done it now.'

Taylor is convinced that, whatever they paid, Everton got a bargain - the best young manager in Britain today. In some ways he is ultra modern, but in a more fundamental sense he is almost a throwback: proud, conservative and cautious. But he is not one to believe the hype, least of all the hype about himself. Moyes sticks with the simple, core values of hard work and cautious progress that have served him well.

In his first day on the job at Bellefield he walked into the changing room and saw the nature of the new challenge. 'David Ginola, Duncan Ferguson and Paul Gascoigne, some of the biggest names in football,' he recalls. 'They were sitting on the bench, looking for direction. I thought, "Jesus Christ. What do I do here?" And then I thought I'd just better do what got me there in the first place. They seemed to think it was OK, what I did, after a while.'

The colour-coded chart in his office tells the same story in a different way. This is a man who judges others and believes absolutely in the accuracy of his own judgment. But he is not going to let his emotions run away with him. The chart is a way of distancing himself from his own subjectivity, a way of externalising and appraising his own thoughts. He wants to see them outside himself, just as he judges a player. But he keeps the meaning of the colour coding to himself. It is the most important part of his office and perhaps an unconscious gesture of his soul - open, but secret.

Wenesday

Jumpers for goalposts

A late start. The players are told to arrive at Goodison at 11, ahead of training on the heated pitch at midday. But the groundsman has watered the goal area, fearful that the pitch would be dried out. Freezing temperatures have turned it to a block of ice; only three-quarters is playable. The masseurs and other back room staff walk over the affected area, mimicking the sloping gait of ice skaters. The groundstaff tell them to **** off.

There is a great deal of deliberation among the managerial team as to how to keep everyone happy. Ferguson is training back at Bellefield. He's not quite fully practice match fit. It would be impossible to have the club captain and a senior pro hanging around on the sidelines.

Goodison is a blue-and-white battleship from the outside which is replicated in the players' tunnel - a close phalanx of blue-and-white panels. Intimidating. Moyes likes that. An elaborate crossing and finishing drill on the usable part of the pitch is followed by a game with one real goal and two jumpers goals at the far end.

The session ends at three.

Irvine goes to see Manchester United host Juventus while Moyes and Lumsden go to Ipswich v Wolves, to watch several players they are interested in. They return north that night, but stay at a Travel Lodge near Warrington, so they can make it to the training ground in good time and save two hours' sleep. The lack of sleep, Moyes says, is a killer.

Still no Rodrigo.