AndyC

Player Valuation: £70m

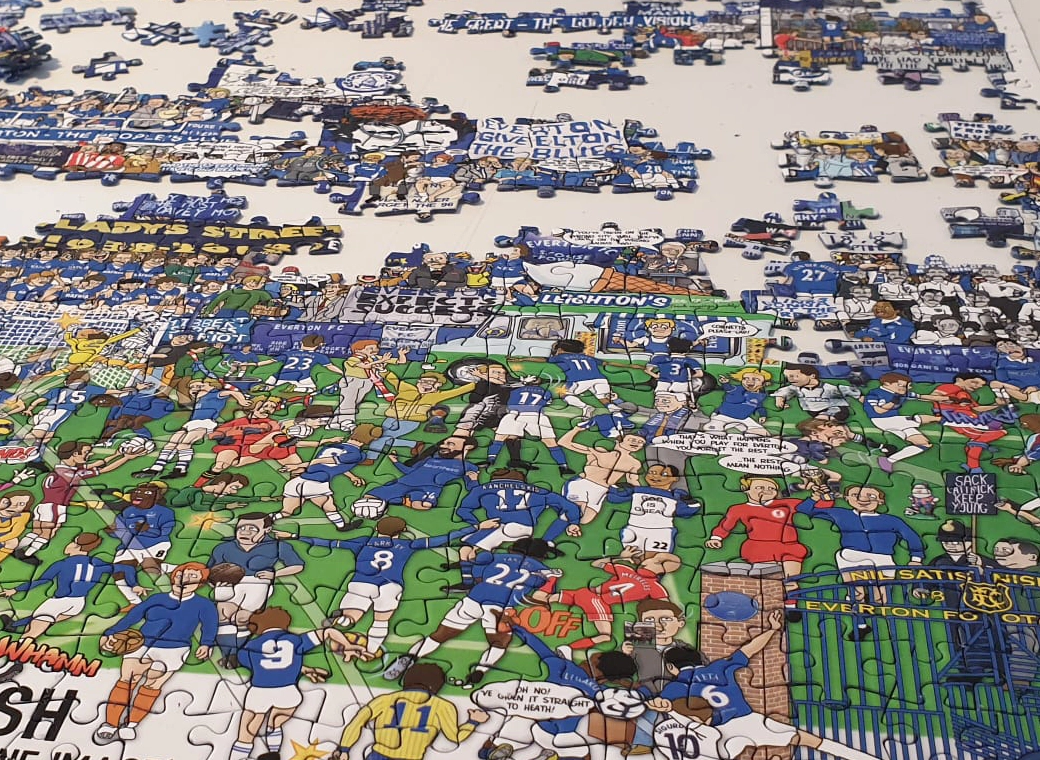

Look closely and you will find the little blue and white plaque on the side of the Goodison Road stand. Nothing too fancy, but at least Everton have something small to mark Harry Catterick, even if they did take their time. The first set of 11 “Everton Greats” plaques was put up in 2000. Catterick was added in 2009 and perhaps it is typical of his life, and the way football appears to have blurred the criteria about what constitutes a managerial great, that it happened with so little fanfare or publicity.

A managerial great? It is easy to imagine a few blank looks at that one. Yet what other way is there to introduce someone who accrued more top-division points during the 1960s than Revie, Busby, Nicholson, Shankly, Mercer or anybody else? And how is it that the man who won two league titles and an FA Cup for Everton and went by the nickname Mr Success, with a nod to the Frank Sinatra song, has become almost a footnote when the list of authentic greats is trotted out?

It would be nice to think something can be done about that now we are approaching the 30th anniversary since Catterick suffered a heart attack in Everton’s directors’ box and, like Dixie Dean five years earlier, died watching the team that had shaped his life.

Then again, football has been so quick to pass over his achievements it is unlikely that the sport will be jolted into too many reminiscences. It is unfair in the extreme, but it has been this way for a long time and Catterick occupies a strange place in football’s annals, embraced by few, rarely mentioned when the sport drifts into nostalgia and the stories of his era are regaled.

Colin Harvey, alongside Alan Ball and Howard Kendall one-third of Everton’s Holy Trinity in those glory years, sums it up in the foreword to a new book about his old manager. “The press enjoyed being courted by Bill Shankly, but Harry was an introvert and snubbed them. As a result, Don Revie, Bill Shankly, Bill Nicholson and Sir Matt Busby all get mentioned as being the great managers of the era while Harry doesn’t. However, he was right up there among them and created three different trophy-winning sides. Over the years I’ve been disappointed he hasn’t received the respect and recognition he deserves.”

It is certainly strange when a veteran of the Merseyside press, Colin Wood, rates the Everton side of 1969-70 as one of the best British teams there has ever been.

Yet the newspapers had Shankly for their soundbites in those days. Catterick was different, deliberately standoffish and reluctant to open his doors, whereas James Mossop, another esteemed football writer of that generation, remembers that “every time Shankly spoke it was original”.

Catterick did not have an endless stock of one-liners and had to be cajoled into writing the most reluctant of programme notes. He insisted Everton’s team lineups were printed in alphabetical order, so the opposition would not have any clues about their formation, and became so obsessed about what came out of the club that when Match of the Day launched in 1964 there is an incredible story of him lobbying Everton’s board to enlist Liverpool’s support and form an anti‑television alliance. Liverpool turned them down so Everton went it alone and banned the cameras until Catterick was eventually overruled. He carried a grudge about it all the way into his retirement years, when, in his darkest moments, he used to complain that Everton were waiting for him to die and paying him to keep away.

It is that dark side that makes his story all the more fascinating and it is remarkable that nobody before Rob Sawyer, the author of Harry Catterick: The Untold Story of a Football Great, has been compelled to put his work into print. The more you learn, the more layers are unpeeled and the more it becomes apparent that David Peace may have chosen the wrong man when he decided on the subject of his follow-up to A Damned United. As much as Shankly is a permanent source of fascination, it was across Stanley Park that the more complex individual could be found, shutters down, operating with a siege mentality that included a training-ground policy of “This is Bellefield, nobody gets in”.

Catterick was difficult, impenetrable, deceitful, frequently unpleasant and pulled some fairly despicable stunts. He was also brilliant, a football visionary, with enough presence that one of his former players recalls “his word was God”.

Harvey makes a valid point when he complains about the way a manager who finished outside the top six once in the 1960s is not more revered. Yet Catterick had erected such a high wall around himself it could not even be said they embraced him at Goodison. While Shankly had messiah-like status at Anfield, Catterick’s relationship with Everton’s fans did not exude anything like the same warmth, culminating in what the club historian, David France, dubbed the “Blackpool Rumble”when 30-40 supporters waited for him after a defeat at Bloomfield Road and, unforgivably, the manager was knocked to the floor.

Catterick, by his own admission, was a “miserable-looking fellow” and he absolutely refused to play the PR game. “The fellow who looks for popularity has something wrong [with him],” he once said.

We are, however, talking about someone who was ahead of his time, calling for a trimming down of a 42-game league, the introduction of professional referees and a more cultured style of football, in the era when teams rejoiced in having men named “Chopper” or “Bite Yer Legs”. Catterick intensely disliked Leeds and Revie and frequently warned that English footballers were in danger of falling behind other European nations. He wore expensively tailored suits, took dancing lessons and developed a taste for expensive cigars and red wine. Yet there was always this Do Not Disturb barrier. Len Capeling, a former sports editor of the Liverpool Daily Post, summed him up, superbly, as someone who “had difficulty in smiling with his eyes”. Shankly knew him as “Happy Harry”.

Catterick could also, in the language of the dressing room, be a bit of a [Poor language removed]. The time, for example, earlier in his managerial career when he was in charge at Sheffield Wednesday and decided one of his players, a smoker, “needed a scare” so arranged for a doctor to check him over, look suitably concerned when he scanned his chest and suggest an X-ray. Or when the team had a night out in Tbilisi, on a tour of eastern Europe, and Catterick started getting hacked off with a local drunk who had been following them around. There was a large roadworks hole near the hotel. Catterick beckoned him to look down it, then raised his foot with the intention of pushing him in and almost certainly would have done until his players intervened.

There is the kindness of the man who wrote a supportive letter to the young Manchester United goalkeeper Ronnie Briggs, who had conceded seven goals against his Wednesday side. Yet Catterick was fearsome, with a boot-camp mentality and a place at the back of the Goodison Road stand the Everton players dubbed the Bollocking Room. “What was he like to play for?” Alex Young, a prolific scorer in the 1962-63 championship season, once said. “Hellish.”

Catterick ended up laughing in Young’s face when the striker left Everton with a gentleman’s agreement for a £1,000 settlement but never saw a penny and “let that be a lesson to you, son: Get everything in writing”.

What an extraordinary story, too, about the night Mike Ellis, the Sun’s Merseyside correspondent at the time, took a rare call from Catterick and – journalistic gold-dust – a tip-off that Liverpool were about to sign Howard Kendall from Preston “and you’ve got that on your own”. What an exclusive. The headline was “Shankly swoops for Kendall” and the player did indeed sign the next morning – for Everton. Catterick had simply wanted to undermine Shankly and when a horrified Ellis tried to get hold of Everton’s manager he was told he was unavailable.

The point, however, is that none of these stories should really matter set against the man’s achievements. They are considerable and Sawyer’s conclusion in a book of meticulous research is that Catterick “unfairly stands in the shadows of contemporaries such as Shankly, Revie and Clough”.

Catterick did not seduce his audiences, but his teams did play with great personality and charisma and it is time, surely, to re-evaluate his work and give him his due.

A managerial great? It is easy to imagine a few blank looks at that one. Yet what other way is there to introduce someone who accrued more top-division points during the 1960s than Revie, Busby, Nicholson, Shankly, Mercer or anybody else? And how is it that the man who won two league titles and an FA Cup for Everton and went by the nickname Mr Success, with a nod to the Frank Sinatra song, has become almost a footnote when the list of authentic greats is trotted out?

It would be nice to think something can be done about that now we are approaching the 30th anniversary since Catterick suffered a heart attack in Everton’s directors’ box and, like Dixie Dean five years earlier, died watching the team that had shaped his life.

Then again, football has been so quick to pass over his achievements it is unlikely that the sport will be jolted into too many reminiscences. It is unfair in the extreme, but it has been this way for a long time and Catterick occupies a strange place in football’s annals, embraced by few, rarely mentioned when the sport drifts into nostalgia and the stories of his era are regaled.

Colin Harvey, alongside Alan Ball and Howard Kendall one-third of Everton’s Holy Trinity in those glory years, sums it up in the foreword to a new book about his old manager. “The press enjoyed being courted by Bill Shankly, but Harry was an introvert and snubbed them. As a result, Don Revie, Bill Shankly, Bill Nicholson and Sir Matt Busby all get mentioned as being the great managers of the era while Harry doesn’t. However, he was right up there among them and created three different trophy-winning sides. Over the years I’ve been disappointed he hasn’t received the respect and recognition he deserves.”

It is certainly strange when a veteran of the Merseyside press, Colin Wood, rates the Everton side of 1969-70 as one of the best British teams there has ever been.

Yet the newspapers had Shankly for their soundbites in those days. Catterick was different, deliberately standoffish and reluctant to open his doors, whereas James Mossop, another esteemed football writer of that generation, remembers that “every time Shankly spoke it was original”.

Catterick did not have an endless stock of one-liners and had to be cajoled into writing the most reluctant of programme notes. He insisted Everton’s team lineups were printed in alphabetical order, so the opposition would not have any clues about their formation, and became so obsessed about what came out of the club that when Match of the Day launched in 1964 there is an incredible story of him lobbying Everton’s board to enlist Liverpool’s support and form an anti‑television alliance. Liverpool turned them down so Everton went it alone and banned the cameras until Catterick was eventually overruled. He carried a grudge about it all the way into his retirement years, when, in his darkest moments, he used to complain that Everton were waiting for him to die and paying him to keep away.

It is that dark side that makes his story all the more fascinating and it is remarkable that nobody before Rob Sawyer, the author of Harry Catterick: The Untold Story of a Football Great, has been compelled to put his work into print. The more you learn, the more layers are unpeeled and the more it becomes apparent that David Peace may have chosen the wrong man when he decided on the subject of his follow-up to A Damned United. As much as Shankly is a permanent source of fascination, it was across Stanley Park that the more complex individual could be found, shutters down, operating with a siege mentality that included a training-ground policy of “This is Bellefield, nobody gets in”.

Catterick was difficult, impenetrable, deceitful, frequently unpleasant and pulled some fairly despicable stunts. He was also brilliant, a football visionary, with enough presence that one of his former players recalls “his word was God”.

Harvey makes a valid point when he complains about the way a manager who finished outside the top six once in the 1960s is not more revered. Yet Catterick had erected such a high wall around himself it could not even be said they embraced him at Goodison. While Shankly had messiah-like status at Anfield, Catterick’s relationship with Everton’s fans did not exude anything like the same warmth, culminating in what the club historian, David France, dubbed the “Blackpool Rumble”when 30-40 supporters waited for him after a defeat at Bloomfield Road and, unforgivably, the manager was knocked to the floor.

Catterick, by his own admission, was a “miserable-looking fellow” and he absolutely refused to play the PR game. “The fellow who looks for popularity has something wrong [with him],” he once said.

We are, however, talking about someone who was ahead of his time, calling for a trimming down of a 42-game league, the introduction of professional referees and a more cultured style of football, in the era when teams rejoiced in having men named “Chopper” or “Bite Yer Legs”. Catterick intensely disliked Leeds and Revie and frequently warned that English footballers were in danger of falling behind other European nations. He wore expensively tailored suits, took dancing lessons and developed a taste for expensive cigars and red wine. Yet there was always this Do Not Disturb barrier. Len Capeling, a former sports editor of the Liverpool Daily Post, summed him up, superbly, as someone who “had difficulty in smiling with his eyes”. Shankly knew him as “Happy Harry”.

Catterick could also, in the language of the dressing room, be a bit of a [Poor language removed]. The time, for example, earlier in his managerial career when he was in charge at Sheffield Wednesday and decided one of his players, a smoker, “needed a scare” so arranged for a doctor to check him over, look suitably concerned when he scanned his chest and suggest an X-ray. Or when the team had a night out in Tbilisi, on a tour of eastern Europe, and Catterick started getting hacked off with a local drunk who had been following them around. There was a large roadworks hole near the hotel. Catterick beckoned him to look down it, then raised his foot with the intention of pushing him in and almost certainly would have done until his players intervened.

There is the kindness of the man who wrote a supportive letter to the young Manchester United goalkeeper Ronnie Briggs, who had conceded seven goals against his Wednesday side. Yet Catterick was fearsome, with a boot-camp mentality and a place at the back of the Goodison Road stand the Everton players dubbed the Bollocking Room. “What was he like to play for?” Alex Young, a prolific scorer in the 1962-63 championship season, once said. “Hellish.”

Catterick ended up laughing in Young’s face when the striker left Everton with a gentleman’s agreement for a £1,000 settlement but never saw a penny and “let that be a lesson to you, son: Get everything in writing”.

What an extraordinary story, too, about the night Mike Ellis, the Sun’s Merseyside correspondent at the time, took a rare call from Catterick and – journalistic gold-dust – a tip-off that Liverpool were about to sign Howard Kendall from Preston “and you’ve got that on your own”. What an exclusive. The headline was “Shankly swoops for Kendall” and the player did indeed sign the next morning – for Everton. Catterick had simply wanted to undermine Shankly and when a horrified Ellis tried to get hold of Everton’s manager he was told he was unavailable.

The point, however, is that none of these stories should really matter set against the man’s achievements. They are considerable and Sawyer’s conclusion in a book of meticulous research is that Catterick “unfairly stands in the shadows of contemporaries such as Shankly, Revie and Clough”.

Catterick did not seduce his audiences, but his teams did play with great personality and charisma and it is time, surely, to re-evaluate his work and give him his due.